Hello!

In our last episode in the section about Caroline Herschel i mentioned i would do a blog on The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago. Well this project is much larger and way more awesome then i knew at the time so i will be covering it in chucks! I hope you enjoy!

I do shorten what is on the website to make it slightly more readable in our format here.

The photos and all information in this post are from the Brooklyn Museum. (Copyright © 2004–2019 the Brooklyn Museum.)

Link to Website: https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/home

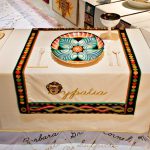

The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago is an icon of feminist art, which represents 1,038 women in history—39 women are represented by place settings and another 999 names are inscribed in the Heritage Floor on which the table rests. This monumental work of art is comprised of a triangular table divided by three wings, each 48 feet long.

The principal component of The Dinner Party is a massive ceremonial banquet arranged in the shape of an open triangle—a symbol of equality—measuring forty-eight feet on each side with a total of thirty-nine place settings. The “guests of honor” commemorated on the table are designated by means of intricately embroidered runners, each executed in a historically specific manner. Upon these are placed, for each setting, a gold ceramic chalice and utensils, a napkin with an embroidered edge, and a fourteen-inch china-painted plate with a central motif based on butterfly and vulvar forms. Each place setting is rendered in a style appropriate to the individual woman being honored.

Wing One of the table begins in prehistory with the Primordial Goddess and continues chronologically with the development of Judaism; it then moves to early Greek societies to the Roman Empire, marking the decline in women’s power, signified by Hypatia’s place setting.

Wing One

Prehistory to Classical Rome

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Primordial Goddess place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Primordial Goddess plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), 15 × 14 × 1 in. (38.1 × 35.6 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(Mythic)

The original conception of the goddess is that of Mother Earth, the sacred female force responsible for the creation of the earth and all its flora and fauna. The goddess was the universal soul, who accepted plant, animal, and human matter in death in order to create new life from the remains.

The tradition of the Mother Earth Goddess can be seen reflected in many different conceptions of the divine feminine including the Greek mother goddess, Gaea, the original inspiration for the Primordial Goddess place setting. Regardless of the many forms she takes that are celebrated globally, all goddess traditions owe something to the early worship of and appreciation for the Primordial Goddess.

Primordial Goddess at The Dinner Party:

The Primordial Goddess place setting references early goddess traditions, in which women were creators, associated with the primordial earth. The plate evokes both flesh and rock, symbolizing the ties between the female body and Mother Earth. Judy Chicago calls the Primordial Goddess the “Primal Vagina,” the original source of all life (Chicago, Symbol of Our Heritage, 57). The coil around the Primordial Goddess’s first initial represents the early baskets and pottery made by women using coil forms. The calfskins represent the early clothing made by women; they are adorned with cowry shells, an ancient symbol of female fertility. Fur, a soft, appealingly tactile material, is also related to the production of clothing and associated with women and women’s work.

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Fertile Goddess place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Fertile Goddess plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), rainbow luster, 14 × 14 × 1 in. (35.6 × 35.6 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(Mythic)

Many societies have worshipped the Fertile Goddess as the supreme site of fertility, motherhood, and the creation of life. Famous pieces, such as the Venus of Lespugue and the Venus of Willendorf are Upper Paleolithic (30,000–10,000 B.C.E.) examples that may have been worshipped as goddesses.

Marija Gimbutas, a leading scholar in the study of early goddess worship, has linked the prehistoric goddess figures to water, having found early female figures incised with symbols denoting water in its various forms, as well as imagery linking rain and streams with breast milk and amniotic fluid. In The Language of the Goddess, considered a significant work in the field, she suggests that these figurines and their associated symbols, found throughout the Neolithic period as well and into the Bronze Age (2000–1400 B.C.E.) in Crete, could represent a goddess religion that was passed down through time.

Fertile Goddess at The Dinner Party:

All the materials on the runner were made with techniques probably used by Paleolithic-era women to produce similar objects. Bone needles were handmade from cow femurs and the wool was spun on a drop spindle, one of the earliest tools invented by women. As in the Primordial Goddess place setting, the coil is the predominant form on the runner; it refers to the early coil baskets and pottery made by women. The coarse burlap used as the backing references early textiles, another product believed to have been produced exclusively by women. As farming marks the start of the Neolithic period and is considered responsible for advancing civilization, the place setting also signifies women’s roles in shaping ancient society.

Many of the formal and stylistic decisions for the runner and plate were influenced by early goddess images, such as the Venus of Willendorf. Figures woven into the runner represent early reproductions of the female body, effigies that were used to worship women as creators and nurturers. Shells and starfish adorn the runner and refer to the association of the sea with women, fertility, and goddesses, such as Venus.

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Ishtar place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Ishtar plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), metallic glaze, rainbow luster, 14 × 14 × 1 in. (35.6 × 35.6 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(Mythic)

Ishtar, called the Queen of Heaven by the people of ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), was the most important female deity in their pantheon. She shared many aspects with an earlier Sumerian goddess, Inanna (or Inana). A multifaceted goddess, Ishtar takes three paramount forms. She is the goddess of love and sexuality, and thus, fertility; she is responsible for all life, but she is never a Mother goddess. As the goddess of war, she is often shown winged and bearing arms. Her third aspect is celestial; she is the planet Venus, the morning and evening star.

As the goddess of sex, Ishtar may have been connected with sexual practice in cults, in a way that is not yet fully understood. Explicit erotic and sexual references do abound in texts concerning Ishtar/Inanna. However, ancient terms for classes of individuals associated with her cult or temple (formerly often translated to “sacred prostitute”) more likely encompass a range of roles in cult rituals that changed over time.

Because of her multiple aspects and powers, Ishtar/Inanna remains a complex and confusing goddess figure in modern study. Scholars suggest she incorporates contradictory forces to the point of embodying paradox: sex and violence, fecundity and death, beauty and terror, centrality and marginality, order and chaos. Ishtar, in all her variety and contradiction, was a central figure in ancient Mesopotamian religion and culture for millennia.

Ishtar at The Dinner Party

Ishtar, the great Goddess of Mesopotamia, is represented at The Dinner Party through architectural motifs. The geometric forms of her runner are taken directly from the Babylonian Ishtar Gate, and the earlier Ziggurat of Ur. The stepped edges mimic the ascending stepped levels of a ziggurat, while the interior edge of the arch is done in brick stitch, a reference to the glazed tiles that cover the Ishtar Gate. The runner is outlined in black braid, which also acknowledges the ancient technique of braiding.

The colors of the plate and runner, mainly shades of gold with green highlights, were chosen as Ishtar’s colors. The gold represents her grandeur and also echoes some of the colors of the Mesopotamian architecture and landscape, while green is her sacred color. On the plate, she is depicted as the positive female creator with multiple breast-like forms that allude to her role as a giver of life. These forms are paralleled in the stitching around the capital letter, done in Italian shading.

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Kali place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Kali plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), rainbow luster, 14 × 14 × 1 in. (35.6 × 35.6 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(Mythic)

Worship of Kali has roots in ancient East Indian belief systems from the first millennium B.C.E. Today Kali is primarily worshipped in Bengal, eastern India, and throughout Southeast Asia in various forms. Kali, whose other names include Sati, Rudrani, Parvati, Chinnemastica, Kamakshi, Umak Menakshi, Himavati, and Kumari, is the fierce manifestation of the Hindu mother goddess, or Great Goddess Devi (also known as Durga). She is a complicated symbol, simultaneously feared and adored. As she is associated with the opposing forces of destruction and death, as well as creation and salvation, she has been characterized as both vicious and nurturing. She serves as a reminder of death’s inevitability, which encourages acceptance and dispels fear. She is also a goddess of fertility and time, and is the protector often called upon during disasters and epidemics. As a symbol of productivity, she represents the cycles of nature, and can also be interpreted as a constant creator, taking life to give new life. As destroyer, Kali kills that which stands in the way of human purity and peace in both life and death, such as evil, ignorance, and egoism. Kali’s name comes from the Sanskrit word for “time,” signifying her presence throughout the course of human life.

Kali is also often portrayed standing over her husband and consort, Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction, with one foot on his leg and another on his chest. This position suggests the narrative of his throwing himself under her feet to stop her spree of destruction. Kali is believed to be the formless energy of Shiva’s demolishing forces; the couple is also often depicted dancing or in sexual union, which suggests Kali is the female counterpart to Shiva; together they represent dynamism and the dualistic nature of the world.

Kali’s plate is painted with central core imagery, which is filled with seed forms symbolizing fecundity and referencing Kali’s association with the cycles of nature. The plate is painted in deep reds, purples, and browns that repeat in the finger-like protrusions stitched into the runner and in the illuminated letter “K.” These colors remind the viewer that the goddess drinks the blood of demons and that her thirst can never be satiated. The rib-like vertical bands on the plate are evocative of her anthropomorphic form, which is typically depicted as emaciated with prominent ribs.

The undulating flanges on the runner were made using layers of sheer iridescent fabrics, called luminaires, which were then covered in shimmering white fabrics to create a pearlescent effect. This layering is suggestive of the flayed skin of a human corpse, a direct evocation of Kali’s power and her role in death. The forms also reference Kali’s multi-armed manifestation. On the back of the runner, the jutting shapes culminate in an illusory, mouth-like opening, or “gaping maw” as Chicago describes it (Chicago, Embroidering Our Heritage, 47). Through the abstract representation of an organic form, Kali’s powers as the Great Destroyer are represented as restorative rather than horrific.

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Snake Goddess place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Snake Goddess plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), rainbow overglaze, gold metallic glaze, 15 × 14 × 1 in. (38.1 × 35.6 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(Mythic)

Because written evidence is scarce, scholars have been forced to rely on ancient Minoan material and visual remains in order to understand the nature of Minoan religion. The goddess is thought to have been worshipped in Crete from circa 3000–1100 B.C.E. Early interpretations of her worship, focused on a domestic cult practiced in houses and palaces. Subsequent excavations have revealed shrines with goddess figures located in towns or certain areas of palaces, suggesting that the sphere of the Minoan goddess extended to the official public arena.

Numerous clay figurines of goddesses and clay ritual equipment found in shrines outside the palace of Knossos suggest that Minoan goddess figures are primarily associated with snakes and birds, although this distinction is not exact and evidence exists for other possible associations. Bared breasts, and the bell shapes of some clay goddess figures, suggest a connection with fertility; the association with snakes evokes a chthonic or underworld aspect as well.

Goddess figurines excavated later at other sites are clay and have simplified forms; they are often known as the “Goddess with upraised arms.” Figures of Minoan goddesses similar to those from Knossos appeared on the antiquities market and some were purchased by museums. Made of ivory, stone, and in one case, of terracotta, their authenticity has been challenged by a scholar in the field, Kenneth Lapatin. Of interest are the ivory examples, particularly those embellished with gold. This technique is known as “chryselephantine,” taken from the ancient Greek words for gold and ivory. A specialist in objects of this type, Lapatin has questioned these examples. At the time of their appearance and for many years thereafter, however, they were hailed as exquisite examples of Minoan sculpture and their colors of ivory and gold are used in the runner for the Snake Goddess in The Dinner Party.

Snake Goddess at The Dinner Party:

The runner is decorated in both ivory and gold with brown and yellow accent colors. The snake motif is apparent in the images of gold snakes on the back of the runner and in the snake intertwined in the letter “S” on the runner’s front. The front of the runner echoes the Cretan figure, with a flounce that mimics that of the goddess’ skirt. Inkle-loom woven strips border the runner and are embroidered with patterns similar to those found in Minoan garments.

The plate is rooted in vulvar (or central core) imagery found throughout The Dinner Party, and is largely based on the color-scheme of Cretan Snake Goddesses statues. Echoing their gold and ivory tones, the plate contains four pale yellow arms growing out from a center form, “whose egg-like shapes represent the generative force of the goddess” (Chicago, A Symbol of Our Heritage, 60).

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Sophia place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- 2-Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Sophia plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), rainbow overglaze, 15 × 15 × 1 in. (38.1 × 38.1 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(Mythic)

The goddess of wisdom has appeared in nearly every society in a variety of different manifestations, including Athena, Greek goddess of wisdom and military victory; Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and war; Tara, the Buddhist goddess of compassion who teaches the wisdom of non-attachment; and Inanna, an early Sumerian Goddess. Sophia, whose name in Greek means “wisdom,” is connected to the different incarnations of sacred female knowledge and to those goddesses listed above.

Sophia is one of the central figures of Gnosticism, a Christian philosophical movement with uncertain origins that most likely originated in ancient Rome and Persia. Its followers worship Sophia as both divine female creator and counterpart to Jesus Christ. According to Gnostic beliefs, Christ was conceived of as having two aspects: a male half, identified as the son of God, and a female half, called Sophia, who was venerated as the mother of the universe.

According to The Apocryphon of John, one of the main texts of Gnosticism dating to circa 180, Sophia represented divine wisdom and the female spirit. She is also celebrated in Kabbalah, a form of Jewish mysticism, as the female expression of God. In nearly all representations of sacred wisdom some aspect of Sophia can be found; she, like many other goddesses, even became integrated into the worship of the Virgin Mary in the Middle Ages.

Since the emergence of the modern feminist movement in the 1970s, Sophia has gained popularity as a figure for goddess worship. There has also been a scholarly effort to locate Sophia historically as the goddess of wisdom within the context of Christian religious practices, texts, and images. One of the most interesting theories relates to Michelangelo’s paintings on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Some scholars and art historians believe that the female figure under God’s left arm in the Creation of Adamis, in fact, Sophia, acting out her role as the female being in the creation of life and man.

Sophia at The Dinner Party:

On the runner, the petals’ vibrancy fades from the edges toward the center, which signifies the waning of female power that followed the development of Christianity. The chiffon netting that veils the flower petals on the runner is intended to make the vibrant fabric underneath look pale, suggesting how life has paled for women since the downfall of the goddess in popular society (Chicago, The Dinner Party, 38).The netting is the wedding veil of Karen Valentine, one of the women who worked on The Dinner Party. The veil is a symbolic reference to marriage, and one interpretation of its presence suggests that marriage is an institution that can be seen as contributing to the decline of women’s societal power.

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Amazon place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Amazon plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), silver metallic glaze, gold metallic glaze, and rainbow luster, 14 × 14 × 1 in. (35.6 × 35.6 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(Legendary)

According to Greek mythology, the Amazons were warrior women living northeast of Ancient Greece during the later Bronze Age, between approximately 1900 and 1200 B.C.E. The source of the Amazonian myths is classical Greek literature, where they were first mentioned by Homer.

There are many legends of the Amazon warriors; in some accounts, they live in an exclusively female society and seek out men only once a year in order to procreate. There are versions that recount their killing, mutilating, or selling their male offspring into slavery. Although there is no conclusive evidence linking these myths to any ancient tribes resembling the Amazons, the subject’s popularity and its representations in art and literature has engendered many successive legends. The Amazon Warrior holds an important place at The Dinner Party, representing a tradition of powerful female warriors and the value of unified communities of women.

Amazon at The Dinner Party:

The Amazon women are represented in the place setting as a symbolic individual. The place setting represents Amazon women both as warriors and as goddess worshippers. The color palette—black, red, and white—is traditionally used in their artistic representation.

On the plate is an image of breasts covered in gold and silver, representing the breastplates that the warriors wore in battle. The image may also refer to the legend that Amazon warriors cut off one of their breasts to be better archers. The plate also depicts two double-headed axes, a white egg, a red crescent, and a black stone, all of which are associated with the Amazons. In addition to their use in battle, double-headed axes were an element of goddess worship in Crete, the center of the Minoan world, 2600–1400 B.C.E., and they were also traditionally used by women to cut down trees. The white egg is a symbol of fertility; the red crescent is tied to the worship of the Great Mother and her connection with the moon; and the black stone was the earliest incarnation of the goddess in Sumer, 3500–2334 B.C.E., present-day Iraq.

The runner echoes much of the same imagery used in the plate—the white egg, red crescents, double-headed axes, and breastplates appear on the back. A triangle, a symbol of the goddess and the sacred feminine, provides a base for the egg and crescents. Snakeskin, on the front of the runner, was a material the Amazons wore into battle. Both the titanium blades of the axes, and the lacing, are tied with French knots made of copper fibers, which come from the studs on the Amazon’s boots. The image of the axe is repeated in the illuminated capital letter “A” on the front of the runner.

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Hatshepsut place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Hatshepsut plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), 14 × 14 × 1 in. (35.6 × 35.6 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(b. 15th century B.C.E., Ancient Egypt; d. unknown)

(Read our coverage of her here. Listen Here)

Hatshepsut reigned over Ancient Egypt as its veritable pharaoh while the official king was still too young to rule effectively. During her reign she adopted a role and title typically reserved for male rulers.

Thutmose III was just a child at the time he was crowned pharaoh, which allowed Queen Hatshepsut to rule alongside Thutmose III as his regent. Despite her legal title as regent, Hatshepsut actively took the pharaonic role, because the king himself was still young. Though this role was traditionally assumed by mothers of young kings, Hatshepsut acted as principal king while Thutmose III was treated as co-regent, a role usually reserved for younger, designated heirs appointed by their fathers. Hatshepsut actively asserted her role as pharaoh and sought to legitimate her rule over Egypt in numerous, highly visible ways. In reliefs she commissioned of herself, she is often represented in the dress of a male pharaoh, even wearing a fake beard; the only indication that she is a woman is her name inscribed beside her image. At other times, Hatshepsut is identifiably female, but wears the royal regalia of a male pharaoh.

A famous series of reliefs at her temple at Deir el-Bahari in the Valley of the Kings, depict Hatshepsut’s divine birth and coronation. In such divine birth scenes, a god—in Hatshepsut’s relief it is the chief god Amun—impregnates the pharaoh’s mother, thus establishing the pharaoh’s rule as a rightful and god-granted part of the divine order of the world. In representing herself as a divine daughter of the gods, she sought to erase any doubts about the legitimacy of her rule as pharaoh.

After her death, Thutmose III, now sole king, emphasized his relationship to Thutmose II, his natural father, and minimized evidence of Hatshepsut’s more than twenty-year dominance during his reign. Despite Thutmose III’s efforts to downplay her role, Hatshepsut is still widely considered to have been the legitimate fifth king of the Eighteenth Dynasty, and her life as a powerful ancient female authority continues to fascinate thousands of years later.

Hatshepsut’s plate is the first at The Dinner Party to have a raised relief surface. It symbolizes the authority Hatshepsut exerted over Egypt as its most renowned female pharaoh. It also mirrors the Egyptian low relief, a popular and important method of sculpting during the Dynastic period, in which figures protrude slightly from the surface, creating contour and visibility. In keeping with that tradition, the center of the plate is only slightly, nearly imperceptibly, raised; according to Chicago, this place setting represents the transition from the flat plates in The Dinner Party to the three-dimensional ones. The plate’s blue and red tones recall colors often seen in Egyptian tomb paintings and reliefs. The smoothly curving shapes in the image suggest Egyptian hairstyles, headdresses, pharaonic collars, and the rendering of partial profiles used repeatedly in Egyptian portraits.

Hieroglyphic symbols praising the pharaoh’s reign were embroidered onto strips of fine white linen, which emulate the high-quality fabric used in Hatshepsut’s time (Chicago, The Dinner Party, 43). The pink and green border on the runner replicates the geometric motif and color palette found in the frescoes in Hatshepsut’s tomb. The blue-green roundlettes on the back of the runner are designed to resemble the same style of pharaonic collar. In ancient Egypt, blue-green was an important color, as it was associated with the deities, and rulers who wore the color visually connected themselves to gods and goddesses. The illuminated letter “H” on the front of the runner combines the Egyptian symbols of the eye of justice and the life-giving symbol of the pharaoh (Chicago, Embroidering Our Heritage, 56). Also on the front of the runner are embroidered symbols “suggesting the phrase: ‘Well-doing Goddess, Just Pharaoh of Egypt’” (Chicago, Embroidering Our Heritage, 61).

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Judith place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Judith plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), 14 × 15 × 1 in. (35.6 × 38.1 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(Biblical)

Judith, whose name translates from the Hebrew as “Jewess” or “Praised,” was a widow of noble rank living in the Jewish city of Bethulia during 6th century B.C.E. During the time when the city was under attack by the Assyrian army headed by Holofernes, Judith is said to have devised a plan to reclaim her land for her people.

Pretending to flee the land of the Israelites, she requested a meeting with Holofernes to discuss a strategy to help his army win. Holofernes was mesmerized by the noblewoman’s great beauty and her desire to serve his army, and he invited her to remain as his guest. After a feast, when she was left alone with the intoxicated general, she and her maid decapitated him with his own sword and carried his head back to the Bethulian people. Her act restored the Israelites’ strength and courage and caused chaos within the Assyrian army. The army quickly fled, and the people of Bethulia were left in peace.

Judith’s story has not fully been accepted as history. Many scholars believe that it is a fictionalization of historical events, while others believe it can be read as a parable. This heroic tale has been depicted throughout history by countless artists, including Donatello, Botticelli, Titian, Michelangelo, and Caravaggio, among others. Perhaps the best-known artistic representation is Artemisia Gentileschi‘s (Read about her here. Listen here.) Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1612–13, painted by one of the first women to take on religious and heroic themes.

Judith at The Dinner Party:

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Sappho place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Sappho plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), 14 × 15 × 1 in. (35.6 × 38.1 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(b. 625 B.C.E., Island of Lesbos; d. 570 B.C.E., location unknown)

Called the Tenth Muse by Plato, Sappho was a prolific poet of ancient Greece. She innovated the form of poetry through her first-person narration (instead of writing from the vantage point of the gods) and by refining the lyric meter. The details of Sappho’s life have been obscured by legend and mythology, and the best source of information is the Suidas, a Greek lexicon compiled in the 10th century.

The community of women on the Isle of Lesbos often gathered to read poetry, perform music, celebrate women’s religious festivals, and collectively welcome their daughters’ first menses. Sappho herself was knowledgeable and skilled in music and dance and enjoyed intertwining these art forms during performances. During this period of Greek history, homosexuality was accepted and relationships between women on the island were common.

Sappho was one of the earliest poets to write vivid and emotional poetry in the first person. Her most common subject was love and the strong emotions it generated, such as passion, jealousy, affection, and hatred. Her poems were recited accompanied by a lyre, which heightened their emotional impact.

Not only was Sappho’s subject matter revolutionary, but her use of language also changed poetry. She wrote solely in the local dialect, using common expressions and words in her poems. She had a graceful and elegant style; the lyric meter that she refined is now called the Sapphic meter, a type of lyric that influenced both Ovid and Catullus. (The form is defined as a stanza of three such verses followed by a verse consisting of a dactyl followed by a spondee or trochee.) While acclaimed during her lifetime, Sappho’s writings were criticized and ultimately destroyed by the church after the 4th century because of their erotic and lesbian imagery. Attempts to revive her poetry began in the Renaissance and have continued throughout history. Well into the 20th century, translations often obscured the lesbian themes in her work. The accompanying legends and mythology that surround her life, as well as a lack of textual remnants of her poetry, have made Sappho a mysterious figure perhaps better known for introducing the terms “lesbian” and “sapphic” into modern vocabulary.

Sappho at The Dinner Party:

Sappho’s place setting incorporates motifs from Greek art and architecture, which reflect her important cultural influence. There are also references to her as the “flower of the graces,” a name which contemporary writers ascribed to the poet.

The plate incorporates vulvar (or central core) imagery, including an abstracted floral form with petals glazed in purples, blues, and greens. The color palette also suggests the Aegean Sea surrounding the Island of Lesbos.

On the back of the runner, the colors of the sea are the backdrop for an embroidered Doric temple. Four wavy lines border the runner, mimicking the long curly hair often found in Greek statues of the Classical period. On the front of the runner, Sappho’s name is embroidered in an eruption of color that identifies her poetry as a “burst of female creativity” (Chicago, The Dinner Party, 68). The “S” in her name is illustrated with a lyre, the instrument that often accompanied the recitation of her poetry.

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Aspasia place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Aspasia plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), 14 × 15 × 1 in. (35.6 × 38.1 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(b. circa 470 B.C.E., Miletus, Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey); d. circa 410 B.C.E., location unknown)

Aspasia of Miletus was a scholar and philosopher whose intellectual influence distinguished her in Athenian culture, which treated women as second-class citizens during the 5th century B.C.E. She used her status to open a school of philosophy and rhetoric, and she is known to have had enormous influence over such prominent leaders and philosophers as Pericles, Plato, and Socrates.

As she was from Miletus, Aspasia was able to circumvent the legal restrictions on Athenian women, who lacked the most basic rights and were sheltered from public life. Whereas the majority of Greek women were illiterate, and would never have been welcomed into the philosophical and academic circles associated with Plato and Socrates, Aspasia arrived in Athens in the mid-440s B.C.E. as an educated woman, schooled by her father, Axiochus. She established an academic center for the exchange of ideas, which served as a school for elite young women in Athens.

Aspasia’s writing, and her knowledge of philosophy and local politics, drew the most powerful citizens in Athens, including notable writers and thinkers, to listen to her lectures. Aspasia was acclaimed for her intellect and charisma, and Socrates, in his writings, credits her as his instructor in rhetoric. Though none of Aspasia’s own writings exist, many of the most famed ancient Greek scholars have featured her in their texts, acknowledging her as their muse.

Her plate shows a blooming floral pattern, suggestive of her femininity, and done in earth tones used in the art and architecture of 5th century B.C.E.

The runner references the types of clothing and jewelry that both men and women wore during Aspasia’s time. One of the most familiar elements of ancient Greek attire, the Greek chiton (similar to a Roman toga) is suggested in the draped fabric on the front and back of the runner. Two embroidered leaf-shaped pins hold the draped fabric to the runner, similar to the jeweled clasps the Greeks would have used to fasten their robes. On the back of the runner are six black palmettes, embroidered as a stylized version of a honeysuckle or palm tree frond, a dominant motif in Ancient Greek paintings, pottery, and architectural detail. The floral vine pattern, stitched in gold, silver, and black on the runner’s edges, mimics motifs found on many Greek vases and urns. This pattern is also repeated in the illuminated letter “A” on the front of the runner.

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Boadaceia place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Boadaceia plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint) and burnished gold, 14 × 14 × 1 3/16 in. (35.6 × 35.6 × 3 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

(b. circa C.E. 25, Celtic Britain; d. circa C.E. 62, Celtic Britain)

Boadaceia is one of many spellings for the name of the famous warrior queen from Celtic Britain, who ruled during the first century, when the Roman Empire was growing and taking over many of the area’s Celtic tribes. Other spellings of her name include Boudica, Boadicea, Buduica, and Bonduca, though a more popular version is Boadicea, which may be a mistranslation from an original manuscript.

Boudica (this spelling is used in an effort to stay as true as possible to her original Celtic name) was married to Prasutagus, king of the Iceni people, a Celtic tribe living in southeastern England (present-day Norfolk). Prasutagus, following tradition, willed his kingdom to the Roman Empire, with the provision that his two daughters be co-heirs. After his death, the Romans annexed his kingdom as though it were conquered territory. The Iceni people’s property was stolen, and Prasutagus’s family treated as slaves. His widow Boudica was reputed to have been beaten by the Roman soldiers and her two daughters raped.

In the year C.E. 60, the Iceni joined with the Trinovantes, a neighboring people, to revolt against the Romans. They chose Boudica, the popular widow of their beloved king, as their leader. After a series of smaller battles in which Boudica’s troops were victorious, they met the full force of the Roman army. The Roman soldiers were far outnumbered by the rebel Celtic forces, but they were better equipped and defeated Boudica and her army after a long battle, which Boudica commandeered from a chariot with her daughters. Boudica’s army was slaughtered, and it was shortly after this battle that she died. There are two historical sources on Boudica’s life—one claims she poisoned herself and the other asserts she died from illness. Historical sources note that she was buried with all the pomp and ceremony accorded the funeral of a great leader.

After researching Boudica, Chicago and her team decided to use powerful Celtic images to represent her as a warrior queen. The patterns on the runner are constructed from felt, which many scholars agree was the first fabric, predating any woven textiles. The felt on the runner was made using the traditional process of compacting wool with water, heat, and pressure. The powerful curvilinear forms encircling the plate “signify both [Boudica’s] personal strength and the Roman encroachment upon her autonomy and power” (Chicago, Embroidering Our Heritage, 80).

On the plate there is a structure similar to Stonehenge, representing the British Isles where her people were from. A stylized golden helmet, also decorated with Celtic patterns, signifies Boudica’s status as a warrior.

Adorning the swirling patterns in the runner are handmade enameled jewels, which could be found on the traditional Celtic jewelry that Boudica would have worn as queen. The embroidered patterns on the runner and in the illuminated letter “B,” were also adapted from designs found on first-century jewelry, shields, and mirrors.

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Hypatia place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

- Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Hypatia plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint) and paint, 13 7/8 × 14 × 1 3/16 in. (35.2 × 35.6 × 3 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

Hypatia of Alexandria was the first woman to make significant advances in the fields of mathematics and philosophy and was also a respected teacher and astronomer. She became a teacher and eventually the head of a Platonist school in Alexandria, known as the Museum of Alexandria, in 400. It was here that she taught and mentored some of the greatest Pagan and Christian minds of the day, including Orestes, the prefect of Alexandria, who later became a close friend. In teaching, Hypatia focused primarily on the work of two Neoplatonic figures—Plotinus, the philosophy’s founder, and his student Iamblichus.

Hypatia resurrected an interest in Greek religion and goddesses. She came to embody the type of science and learning equated with pagan teachings, such as astrology and numerology, and was an ardent supporter of Greek thought and philosophy. It is unclear whether she conducted her own mathematical research, but she furthered the efforts of established men in the field, her most extensive work being in algebra.

In an environment that was turning increasingly Christian, Hypatia’s sex was less controversial than her Paganism. Most scholars during her time converted from Paganism to Christianity in order to protect themselves against religious hostility. Hypatia refused and continued to teach Pagan beliefs, which made her a target for violence. She became the focal point in a series of riots between Christians and Pagans. The rioting increased, and Hypatia was murdered by radical Christian monks in 415, who stripped her of her clothes, scraped her flesh from her bones, tore off her limbs, and burned her mutilated body.

Hypatia at The Dinner Party:

The runner is bordered with woven bands of wool with interlacing patterns as well as heart motifs similar to those found in the ornamentation of Coptic tunics. The orange, red, and green palette used in the runner is repeated in Hypatia’s plate, which incorporates a leaf motif also based on those found in Coptic tapestries. The plate’s imagery can also be interpreted as a butterfly form; the scalloped edges of the lower wing segments give the illusion of motion. Chicago suggests that this reference to flight, as well as the form’s raised relief, refers to Hypatia’s attempt to “break free from the constraints imposed upon so many women of her time” (Chicago,The Dinner Party, 58).

Embroidered on the back of the runner are four crying female faces from youth to old age that represent Hypatia in the Coptic style, suggesting that she stood for women of all ages. The image’s blurred appearance, and the depiction of four limbs being pulled in different directions represents the brutality of Hypatia’s death and the conflict created by her religious beliefs. Chicago uses a blood-red color in this panel, along with a rainbow of tones, which suggests the dichotomy of violence and beauty in Hypatia’s life.

A rendering of Hypatia’s face, based on an actual Coptic weaving of a goddess, peers through the capital “H” in her illuminated letter. Her mouth is covered in a band, which represents her silencing as well as the “deliberate muting of other powerful women” (Chicago, The Dinner Party, 58).

Pingback: The Dinner Party – Wing 2 – Part 1 – Wining About Herstory

Pingback: The Dinner Party – Wing 2 – Part 2 – Wining About Herstory